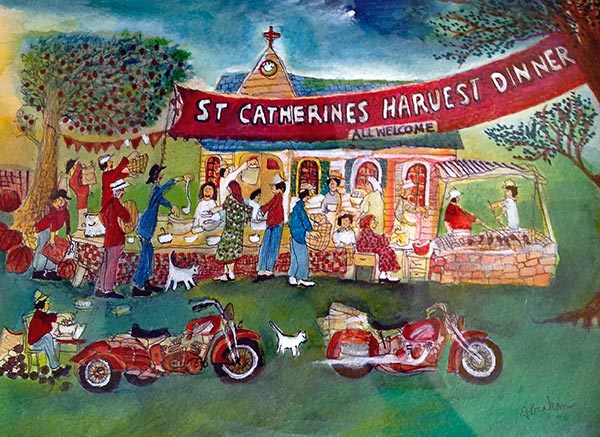

Harvest Dinner, watercolor on paper

Harvest Dinner, watercolor on paper

Jerusalem Landscape with Western Wall, watercolor on paper

Jerusalem Landscape with Western Wall, watercolor on paper

Whenever we use the terms "naïve," "outsider," "primitive," or "folk" in describing art, we find ourselves on a very slippery slope indeed. The difficulty lay in the fact that each term communicates a different, and sometimes contradictory, aspect of the subject. Perhaps the only point of agreement is that all the terms define an oppositional concept to "fine art." "Naïve" suggests that the artist / creator is simply ignorant of the technical properties which define "fine" or traditional art: ignorant, for example, of methods for constructing perspective or scale, of ways of modeling volume in space, or of the properties of color which create harmony or discord. "Outsider," by contrast, speaks more to the political aspects of the work. It is "outside" the formal establishments of the art world: outside the schools, salons, academies, and museums of fine art. "Outsider," thus, implies an anti-elitist point of view. "Primitive" and "folk" suggest a social dimension of the subject, though here too there is a fundamental difference in that "folk" implies an economic status and "primitive" an historical status. "Folk art" is the work of lay artisans and "primitive art" the product of emergent cultures. And, of course, underneath it all is the problem of defining what is or is not "art."

Taken literally, all these terms fail us, and their failure has become increasingly evident in the last half-century. Can an art be considered "primitive," for example, when it is produced by artists in the most technically advanced nations of the world? Can it be considered "outsider" when it hangs in the finest galleries and museums? Can it be considered "naïve" when produced by academically trained artists? In the context of Post Modern and post-Post Modern art, such labels become misleading if not downright meaningless. Unless, that is, we regard the terms not as having historical, social, or political significance but as being merely different approaches to a single concept of style.

Critics have been known to complain of trained artists who practice a "naïve" or unschooled style as being somehow inauthentic. Such criticism is itself naïve, in the opinion of this writer, in that it misses the point that "naïve" art is a style of art that can be adopted by artists skilled or unskilled alike. The only difference is that unskilled artists may have no choice in its adoption. A poor metaphor perhaps, but condemning a skilled artist who adopts an unskilled style is like condemning a virtuous man who chooses not to sin while approving one who simply lacks the opportunity.

Among the Trees, watercolor on paper

Among the Trees, watercolor on paper

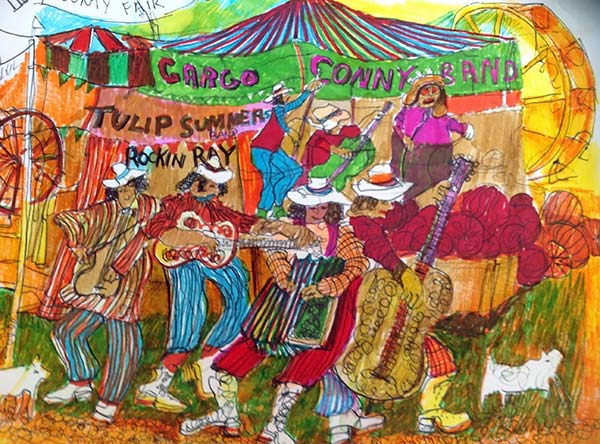

Cargo Conny Band, watercolor on paper

Cargo Conny Band, watercolor on paper

Darryl Abraham is an artist for whom the naïve style is not a necessity. Having received an extensive formal education in art and having taught in several leading universities, Abraham adopted the style as a matter of choice and has practiced the style throughout his long artistic career. A brief consideration of his work, therefore, may help to define the key characteristics of the naïve style and to better understand its pervasive appeal today.

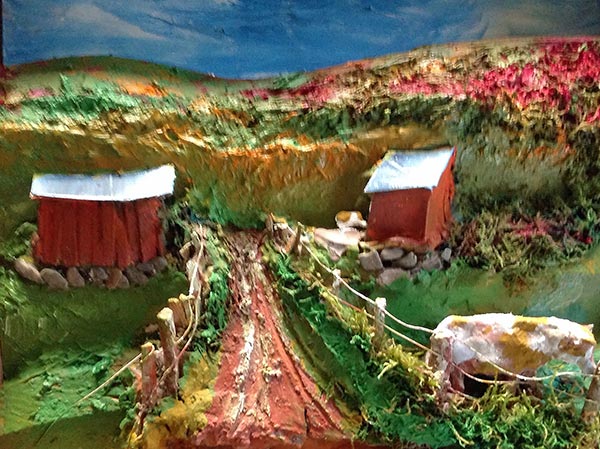

Abraham never seems constrained by any decorum regarding the media in which he works. This would seem to align him with many contemporary artists who find virtually any substance or material an acceptable medium for artistic expression: who, in fact, seek unusual combinations of materials in a quest for originality. Yet for Abraham, this eclecticism is more backward-looking than forward-looking. From his various materials, he fashions what might best be described as 'tableaux', three dimensional scenes usually of rural life. The subjects of these tableaux are quaint. They show ordinary people involved in quotidian tasks, such as farming, fishing, maple sugaring, church going or dancing at the local bar. The tone of the work is gently humorous but never ironic or condescending. The people and activities depicted are uplifting in their unaffected simplicity.

This simplicity of the scene represented is also embodied in the manner with which the tableaux are composed. The artist uses wood, metal, paint, glue, nails, and various unorthodox materials at his disposal in assemblies which belie the expertise with which they are crafted. Their manner of composition reminds us of the freedom of experimentation a child might exercise when constructing 'scenes' from any assortment of available materials. The tableaux hearken back not only historically to an artisanal past but personally to a state of youthful innocence. They are most aptly characterized by a sense of "play."

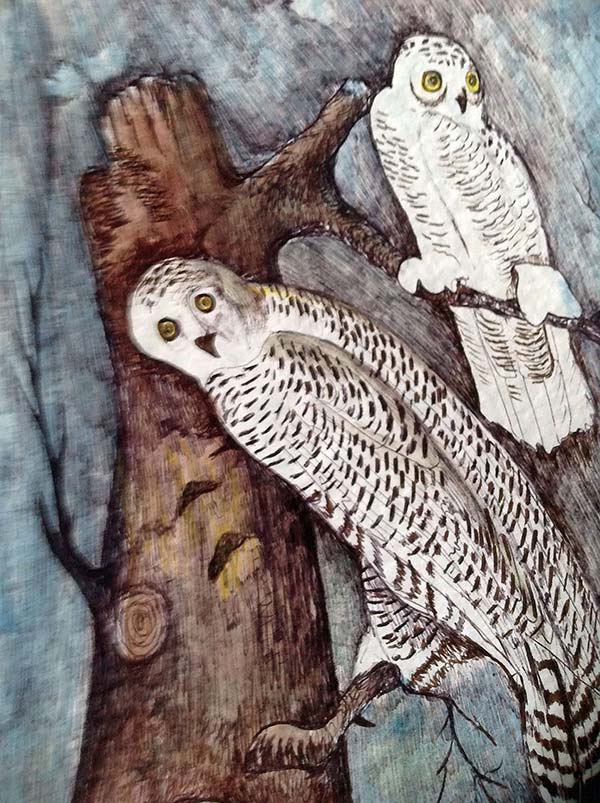

The same spirit pervades Abraham's prints, drawings, and paintings. His etchings eschew the clean boundaries and fine registration of more "sophisticated" prints and seem, at times, as rough-hewn as his tableaux. And their subjects, such as song birds or trophy fish, are as hackneyed as their manner of presentation. They speak to an unaffected pleasure in simple things and gently mock our canons of taste in art. The subject matter of his watercolor paintings, likewise, invariably involves common people doing common things. Even his recent scenes of the Holy Lands, where he lived and worked for several years, betray nothing of the ethnic strife which we have come to associate with the area nor of the technological complexity of modern Israel. They are scenes of a traditional lifestyle, of folkways which have existed for centuries.

Abraham's watercolor paintings are, however, scarcely "paintings" in any conventional sense of the term, the paint being an ancillary part of the composition. Form here is defined entirely by line, and the line is simple and cursory. The paintings are flat, with the only sense of volume or spatial recession being juxtaposition and scale. And scale itself is usually out of all proportion. The color is laid in with a clear artificiality and often overlaps the boundaries of the drawn forms. The overall effect, once again, is to simulate the experience we all remember from our earliest attempts at representing something.

And this speaks to a fundamental – perhaps the fundamental – aspect of "naïve" art. It aims not to realistically represent but to invoke, and what it invokes is a state of innocence. The flatness of the paintings is no obstacle to viewers who, increasingly throughout the last century, have come to associate flatness with modernity in art, while the complexity of modern life often makes us yearn for that which is simple and straightforward. Naïve art recalls to us the state of childhood innocence, a state where the world around us was immediate, tangible, and uncomplicated and where our response to it was one of joy and discovery.

On a subtle level, the naïve style works much like the painted sketch, the two having a great deal in common. Like the sketch, the naïve style moves the viewer's awareness away from the thing represented and the techniques of representation and closer to the logic of the composition. In the naïve style, as in the sketch, our view is closer to the artist's eye, and we experience more intensely his/her original inspiration in the scene. Whether in two or three dimensions, Darryl Abraham's work puts in touch with the basic urge to see the world around us with fresh eyes and to set it forth for display. It recalls within us the instinctual urge to create.

Owls, hand-colored etching on paper

Owls, hand-colored etching on paper

Sugar Shack, mixed media sculpture

Sugar Shack, mixed media sculpture

Farm Road in Three Dimensions, mixed media on board

Farm Road in Three Dimensions, mixed media on board

Prices available on request